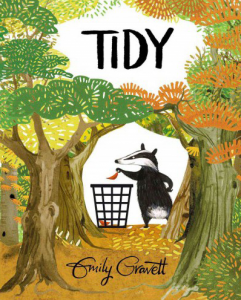

Pete the badger is obsessively tidy. It’s bad enough that his obsession encroaches on his friends personal space but then he turns his attention to cleaning up the environment… and when scrubbing and polishing rocks and picking up every single fallen autumn leaf creates a mound of plastic bags and results in the trees looking “bare and scrappy” he takes things even further. Pete’s extreme cleansing measures, as well as destroying many creatures habitat, result in him being unable to find his way home and after a hungry night spent in the bowl of a cement mixer, he finally sees his mistake. It really helps to pay close attention to the images in this story. The expression on the animals faces as Pete gives them a bath, the flower in the bin, the pile of bin bags, the hoover in the forest, the price tags on the trees…

Pete the badger is obsessively tidy. It’s bad enough that his obsession encroaches on his friends personal space but then he turns his attention to cleaning up the environment… and when scrubbing and polishing rocks and picking up every single fallen autumn leaf creates a mound of plastic bags and results in the trees looking “bare and scrappy” he takes things even further. Pete’s extreme cleansing measures, as well as destroying many creatures habitat, result in him being unable to find his way home and after a hungry night spent in the bowl of a cement mixer, he finally sees his mistake. It really helps to pay close attention to the images in this story. The expression on the animals faces as Pete gives them a bath, the flower in the bin, the pile of bin bags, the hoover in the forest, the price tags on the trees…

How does Pete decide which flowers should stay and which should go?

What is the difference between a weed and a flower?

What is beauty?

Can nature be ugly?

Why do the animals allow Pete to wash them?

Should Pete use the hedgehog to brush the fox’s tail?

Why do the replanted trees have prices tags?

What does it mean to be perfect?

Do some creatures have more rights than other creatures?

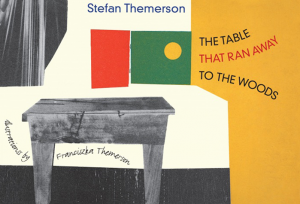

This small format picture book written in 1930’s poignantly tells the story of how the author’s writing desk puts on two pairs of shoes, (a pair belonging to him and a pair belonging to his wife) and takes off down the stairs out of a man-made urban environment and back to the woods where it takes root.

This small format picture book written in 1930’s poignantly tells the story of how the author’s writing desk puts on two pairs of shoes, (a pair belonging to him and a pair belonging to his wife) and takes off down the stairs out of a man-made urban environment and back to the woods where it takes root.