Picture books allow us to suspend our disbelief and imagine ourselves and the world differently. That is why they make great jumping off points for philosophical conversations (read why do philosophy with children here). This blog contains a selection of picture books that raise philosophical questions. Use them as springboards into the unexplored parts of you and your children’s imagination – your great unthunk. I have written some hints at philosophical themes and questions that might arise. Remember these are only some ideas to get you started, each book will suggest different questions to everyone.

Picture books allow us to suspend our disbelief and imagine ourselves and the world differently. That is why they make great jumping off points for philosophical conversations (read why do philosophy with children here). This blog contains a selection of picture books that raise philosophical questions. Use them as springboards into the unexplored parts of you and your children’s imagination – your great unthunk. I have written some hints at philosophical themes and questions that might arise. Remember these are only some ideas to get you started, each book will suggest different questions to everyone.

Between Tick and Tock by Louise Greig and Ashling Lindsay

In a grey bustling city there is no time stop the roundabout to make friends, or notice a lost toy rolling under a park bench or help a stray dog or a stuck cat. But high in the rooftops where the birds roost, Liesel seems to stand outside of time and has the power to make the city pause for a moment. She uses this superpower to stop the clock between ticks and go paint a colourful mural, arrange an accidental encounter so that two children can become friends. She finds the toy and rescues the stray dog and generally intervenes to help people stop and take stock, to notice what’s going on around them. Between Tick and Tock is a meditation on how easy it is to get lost in the day to day and forget to marvel at the world. It raises philosophical questions on the nature of time.

In a grey bustling city there is no time stop the roundabout to make friends, or notice a lost toy rolling under a park bench or help a stray dog or a stuck cat. But high in the rooftops where the birds roost, Liesel seems to stand outside of time and has the power to make the city pause for a moment. She uses this superpower to stop the clock between ticks and go paint a colourful mural, arrange an accidental encounter so that two children can become friends. She finds the toy and rescues the stray dog and generally intervenes to help people stop and take stock, to notice what’s going on around them. Between Tick and Tock is a meditation on how easy it is to get lost in the day to day and forget to marvel at the world. It raises philosophical questions on the nature of time.

Is the flow of time just a human invention, something we just read on a clock?

Does it really exist?

Is time infinite? Or is there a beginning and an end to time?

What happens when the present moment becomes past?

Could it be possible to step outside of time?

Do we need time?

What does it mean to waste time?

How do you know you are in the present?

Do the past and the future exist?

Does time pass more quickly or slowly at depending on what you are doing?

On Sudden Hill by Linda Sarah and Benji Davis

Birt and Etho are BIG friends. Playing together they let their imaginations sore and cardboard boxes become castles, yachts, rockets and space ships. Birt loves their two-by-two rhythm. Then one (cold) Monday morning a tiny boy named Shu comes along. He has been watching them play from afar and has finally plucked up the courage to ask if he can join in too – he has brought his cardboard box. Two become three, Etho welcomes Shu – but Birt feels strange …

Birt and Etho are BIG friends. Playing together they let their imaginations sore and cardboard boxes become castles, yachts, rockets and space ships. Birt loves their two-by-two rhythm. Then one (cold) Monday morning a tiny boy named Shu comes along. He has been watching them play from afar and has finally plucked up the courage to ask if he can join in too – he has brought his cardboard box. Two become three, Etho welcomes Shu – but Birt feels strange …

Two’s company, three is a crowd – a beautiful story raising philosophical questions about the nature and value of friendship.

What makes a good friend?

Is friendship a gift given freely or do we expect something in return for our friendship?

Is it possible to be lonely in a crowd?

Do we need friends to lead a good life?

Do friends shape who we are and who we will become?

What is the difference between being alone and being lonely?

Town is by the Sea by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith

It goes like this – a boy lives with his family in a house by the sea. It’s summer and the sea is sparkling. The boy and his friend play on the only two swings that are left, there used to be four. He runs an errand for his mother. He visits his grandfather’s gravestone.

It goes like this – a boy lives with his family in a house by the sea. It’s summer and the sea is sparkling. The boy and his friend play on the only two swings that are left, there used to be four. He runs an errand for his mother. He visits his grandfather’s gravestone.

All the while the bright summer day is contrasted with the deep dark mine under the sea in which his father works as a coal miner, like his grandfather had done before him and in which, the boy understands he will work too.

In this town, that’s the way it goes.

This book is perfectly described by the New York Times as “quietly devastating.” It raises questions around themes of destiny, free will and determinism and the ethics of work.

published in the UK by Walker books

Why does the boy think he will become a miner?

Does he have a choice?

Does everyone have the same opportunities in life?

Should they?

Are we all born equal?

Should people ever have to risk their life to earn a wage?

There’s a Bear on my Chair by Ross Collins

A rather large polar bear has taken up residence on a very small mouse’s chair. The mouse does everything he can think of to get the bear to move, pushing and shoving, staring him out, luring with delicious fruit… The mouse even tries frightening the bear by jumping out of a box (in his rather unsightly green underpants) to no avail. The bear won’t budge. Then the tables are turned as the bear reveals his endangered status and suddenly we become unsure of what’s right and what’s wrong.

A rather large polar bear has taken up residence on a very small mouse’s chair. The mouse does everything he can think of to get the bear to move, pushing and shoving, staring him out, luring with delicious fruit… The mouse even tries frightening the bear by jumping out of a box (in his rather unsightly green underpants) to no avail. The bear won’t budge. Then the tables are turned as the bear reveals his endangered status and suddenly we become unsure of what’s right and what’s wrong.

Quite often with picture books for the best philosophical questions it’s best to stop before the end of the story, before all the loose ends are tidied up. This is one of those books. Personally I would stop reading just after the bear reveals his endangered status.

Do all creatures have rights?

Do smaller, less powerful creatures have less rights than bigger, more powerful creatures?

Does this apply to younger creatures, what about children?

Do children have the right to property?

What does it mean to have power over someone else?

Should creatures other than humans have legal rights?

Should habitats have rights? Why?

Tidy by Emily Gravett

Pete the badger is obsessively tidy. It’s bad enough that his obsession encroaches on his friends personal space but then he turns his attention to cleaning up the environment… and when scrubbing and polishing rocks and picking up every single fallen autumn leaf creates a mound of plastic bags and results in the trees looking “bare and scrappy” he takes things even further. Pete’s extreme cleansing measures, as well as destroying many creatures habitat, result in him being unable to find his way home and after a hungry night spent in the bowl of a cement mixer, he finally sees his mistake. It really helps to pay close attention to the images in this story. The expression on the animals faces as Pete gives them a bath, the flower in the bin, the pile of bin bags, the hoover in the forest, the price tags on the trees…

Pete the badger is obsessively tidy. It’s bad enough that his obsession encroaches on his friends personal space but then he turns his attention to cleaning up the environment… and when scrubbing and polishing rocks and picking up every single fallen autumn leaf creates a mound of plastic bags and results in the trees looking “bare and scrappy” he takes things even further. Pete’s extreme cleansing measures, as well as destroying many creatures habitat, result in him being unable to find his way home and after a hungry night spent in the bowl of a cement mixer, he finally sees his mistake. It really helps to pay close attention to the images in this story. The expression on the animals faces as Pete gives them a bath, the flower in the bin, the pile of bin bags, the hoover in the forest, the price tags on the trees…

How does Pete decide which flowers should stay and which should go?

What is the difference between a weed and a flower?

What is beauty?

Can nature be ugly?

Why do the animals allow Pete to wash them?

Should Pete use the hedgehog to brush the fox’s tail?

Why do the replanted trees have prices tags?

What does it mean to be perfect?

Do some creatures have more rights than other creatures?

The Bad Mood & The Stick by Lemony Snicket and Matt Forsythe

A girl named Curly is in a bad mood and happens to come across a stick which has randomly fallen to the ground. The stick comes in handy for poking her little brother and happily also relieves her of her bad mood – which has been now passed to her mum. The bad mood is passed on further and so is the stick the stick finds an unlikely home in an ice cream parlour window whose owner keeps it there because it makes him happy.

A girl named Curly is in a bad mood and happens to come across a stick which has randomly fallen to the ground. The stick comes in handy for poking her little brother and happily also relieves her of her bad mood – which has been now passed to her mum. The bad mood is passed on further and so is the stick the stick finds an unlikely home in an ice cream parlour window whose owner keeps it there because it makes him happy.

Where do moods come from?

What are emotions?

What is the difference between a mood and an emotion?

Is a mood a thing that can be transferred/ passed along like a ball?

Is weather a good metaphor for moods?

Do we need our emotions to make reasoned judgements?

Why does the stick make the man happy?

How we respond to objects and incidents via emotions seems to shape what happens next, if we are not in charge of our responses – are we really making decisions for ourselves?

What place do random events have in life? Is the path of our life determined by prior events and experiences rather than by us making reasoned decisions?

Can bad actions have good effects?

If a bad action results in a good outcome – was it still a bad thing to do? How do we determine what is good and what is bad?

if everything that happens to us is a result of some event that happened before – what would be the first cause?

What is a coincidence?

What does it mean when the illustrations are described as art – are illustrations art? Can art be something that is mechanically reproduced?

Her Idea by Rilla Alexander

Sozi has an idea, in fact she has hundreds of ideas but they are slippery and illusive and when she comes to turn her ideas into reality she finds it’s not so easy. Then a passerby offers some hope. The passerby is a book which looks very much like the one that you are holding in your hands (more so if you remove the dust jacket). It helps capture her ideas and keep them safe until she is ready to do something with them.

Sozi has an idea, in fact she has hundreds of ideas but they are slippery and illusive and when she comes to turn her ideas into reality she finds it’s not so easy. Then a passerby offers some hope. The passerby is a book which looks very much like the one that you are holding in your hands (more so if you remove the dust jacket). It helps capture her ideas and keep them safe until she is ready to do something with them.

Alexander captures the trickiness of the process of turning ideas into art. And how it takes hard work (stretching and pulling and cutting) to transform ideas into something more tangible, in this case a picture book. It very cleverly plays on the slippery notion of what is real and what is in your imagination and how ideas are transported from one person to another through the physical medium of the book.

Sozi demonstrates that you don’t have to know how things will end when you embark on a creative endeavour. As it turns out, her ending to the story turns out to be a beginning – the story of how Sozi got to be in the book you are holding in the first place. Like a Russian doll, Sozi becomes a character in the book within the book. Sozi is transformed from author/narrator to idea. Or was she always an idea that we, through reading, turned to something more tangible for a moment?

Can stories trick us? Is it the same as lying?

Are ideas real?

Are ideas better that reality?

Do we distort them when we make them tangible?

Is there a world of ideas more perfect than physical reality?

What is perfection?

Where do ideas come from?

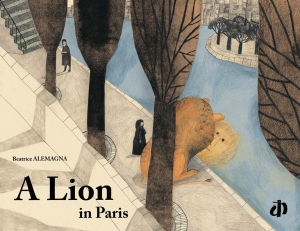

A Lion in Paris by Beatrice Alemagna

A lion, big curious and bored decides to leave the grasslands in search of something more – a job, love and a future. Arriving in Paris by train he is a little daunted by the busy city. He thinks that he might surprise the Parisians but instead they surprise him – by taking no notice. As he takes in more and more of Paris he grows to love the city and decides finally to give up his freedom and his grassland home for a plinth in the middle of a busy roundabout.

A lion, big curious and bored decides to leave the grasslands in search of something more – a job, love and a future. Arriving in Paris by train he is a little daunted by the busy city. He thinks that he might surprise the Parisians but instead they surprise him – by taking no notice. As he takes in more and more of Paris he grows to love the city and decides finally to give up his freedom and his grassland home for a plinth in the middle of a busy roundabout.

Alemagna’s art work – a mixture of color pencil, ink pen, and photo montage is reminiscent of the Table That Ran Away to the Woods. The book opens like a calendar – quite different from usual. So big it’s too awkward to read sitting on your lap. It’s bulk forces us to pay proper attention, spreading it on the table or floor so as to take in each of the beautiful images. Each image is given it’s own page so the pace of the book is deliberate, slow and thoughtful. The text sits on the page above engulfed in white space, encouraging us to contemplate image and text separately.

Does a lion have a job? Did people always have jobs?

What is work? Why should we work?

Could a lion live freely in the city? Can we live freely in the city?

What determines who we are and what we should do?

What makes something real? Does something have to be seen to be real?

What is freedom – is it important?

Does living in a community necessarily mean relinquishing some freedom?

Are we exercising freedom when we choose to give up some freedoms?

What makes a good life?

What is the function of art? Does it have a function?

Is it possible to change our destiny?

Is to be loved more important than to be free?

Sam and Dave Dig a Hole by Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen

Sam and Dave dig a hole next to an apple tree just outside a house. There is a cockerel weathervane on the roof and a red tulip in a pot balanced on the railing. A grey cat with a red collar watches. A dog joins Sam and Dave on their mission to dig until they find something spectacular. They dig and dig and each time they are on the brink of discovery they change direction and miss out. But something spectacular does happen and they land back where they started or do they? Sam and Dave seem unaware as they go inside for chocolate milk and animal biscuits that a few things are different.

Sam and Dave dig a hole next to an apple tree just outside a house. There is a cockerel weathervane on the roof and a red tulip in a pot balanced on the railing. A grey cat with a red collar watches. A dog joins Sam and Dave on their mission to dig until they find something spectacular. They dig and dig and each time they are on the brink of discovery they change direction and miss out. But something spectacular does happen and they land back where they started or do they? Sam and Dave seem unaware as they go inside for chocolate milk and animal biscuits that a few things are different.

Klassen’s illustrations use muted, earthy colours, they seem to be drawn with coloured pencils. Each page contains a lot of white space. Inviting the reader’s imagination to fill the void. The end papers at either side of the book are a different colour and mirror the colour of the fruit on the fruit trees. They indicate change. In most of the drawings the characters are mouthless.

The story builds anticipation and frustration with every near miss. The ending is very ambiguous and perhaps a little unnerving. It has a slightly numbing effect as we search for an explanation and none is given.

Sam and Dave seem annoyingly single-minded, they have tunnel vision. This adds to our sense of frustration and raises questions around how we know things. The text seems as oblivious to the real story as Sam and Dave but if we are using our senses and are tuned into colour and image and the body language of the non-human characters, we see that things are the same yet different. The author gives us no clue as to what has happened.

Are diamonds more valuable than food?

How do we know things?

How does the dog know there are diamonds and bones? Why don’t Sam and Dave?

Should we trust our senses?

Should we trust reason?

The dog finds a bone and seems to trigger a shift in reality and they all fall into a different world, the same but changed. As they fall we see multiple versions of each character.

How do we know which one is real?

How do we know we are real?

Do parallel universes exist?

Are they dreaming?

Is one home less real than the other?

Is it the authors duty to make sense, to answer the questions s/he raises?

Are we a different person at the end of the book than at the start?