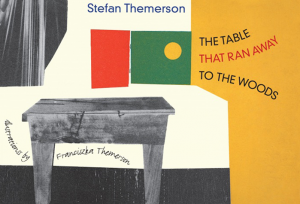

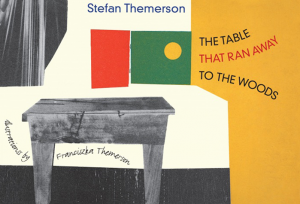

This small format picture book written in 1930’s poignantly tells the story of how the author’s writing desk puts on two pairs of shoes, (a pair belonging to him and a pair belonging to his wife) and takes off down the stairs out of a man-made urban environment and back to the woods where it takes root.

This small format picture book written in 1930’s poignantly tells the story of how the author’s writing desk puts on two pairs of shoes, (a pair belonging to him and a pair belonging to his wife) and takes off down the stairs out of a man-made urban environment and back to the woods where it takes root.

The illustrations were created by the author’s wife Franciszka Themersen. Her technique is collage and photomontage. Images from magazines, and flat colour are in interspersed with hand drawn line on cut-out scraps of paper. Collage with it’s collision of different techniques draws attention to the process of it’s making. Rather than allowing us to become immersed in the illustration it continually draws us back to the surface of the page. The images of the urban scenes are black and white, jagged shapes and cuts outs of concrete brutalist buildings. Colour is rare: the window on the cover, the green leaves, selected words in the text – it’s a welcome relief from the harsh black.

The book is unsettling. There are so many conflicts and contrasts, jarring imagery induces the sense of anxiety the author might have felt at the beginning of an era where war threatens to destroy everything worth fighting for and modernity threatens to turn nature into a resource.

Is there a conflict between nature and culture?

Is culture natural?

Is the state of nature something perfect to be protected from the polluting influence of culture? (Rousseau)

It also raises philosophical questions regarding environmental ethics, modernity’s anthropocentric view of nature as resource.

Is nature simply there for us to do as we please with?

Is it right that human affairs spill out to the detriment of other living things?

The images of branches springing from where the ink has been spilled and the starlings nesting in the inkwell raise questions around language. The starlings in ink seems reminiscent of birds drenched in oil.

Do words restrict, and therefore distort/pollute ideas?

And yet, the word starling suggests the birth of an idea. It’s the fertility of the authors imagination that’s sprouted branches and is about to take flight, remaking the world.

How can ideas (something non physical that arise in the mind) alter the world physically?

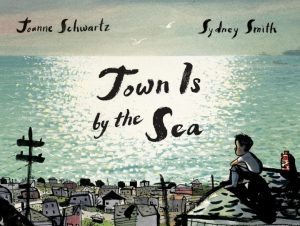

It goes like this – a boy lives with his family in a house by the sea. It’s summer and the sea is sparkling. The boy and his friend play on the only two swings that are left, there used to be four. He runs an errand for his mother. He visits his grandfather’s gravestone.

It goes like this – a boy lives with his family in a house by the sea. It’s summer and the sea is sparkling. The boy and his friend play on the only two swings that are left, there used to be four. He runs an errand for his mother. He visits his grandfather’s gravestone.

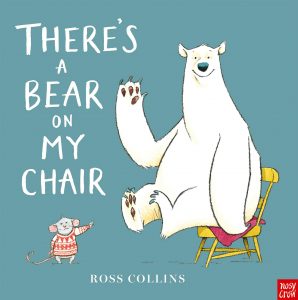

A rather large polar bear has taken up residence on a very small mouse’s chair. The mouse does everything he can think of to get the bear to move, pushing and shoving, staring him out, luring with delicious fruit… The mouse even tries frightening the bear by jumping out of a box (in his rather unsightly green underpants) to no avail. The bear won’t budge. Then the tables are turned as the bear reveals his endangered status and suddenly we become unsure of what’s right and what’s wrong.

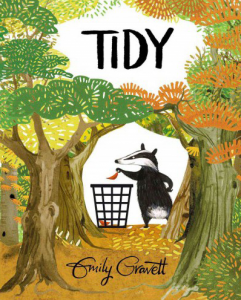

A rather large polar bear has taken up residence on a very small mouse’s chair. The mouse does everything he can think of to get the bear to move, pushing and shoving, staring him out, luring with delicious fruit… The mouse even tries frightening the bear by jumping out of a box (in his rather unsightly green underpants) to no avail. The bear won’t budge. Then the tables are turned as the bear reveals his endangered status and suddenly we become unsure of what’s right and what’s wrong.  Pete the badger is obsessively tidy. It’s bad enough that his obsession encroaches on his friends personal space but then he turns his attention to cleaning up the environment… and when scrubbing and polishing rocks and picking up every single fallen autumn leaf creates a mound of plastic bags and results in the trees looking “bare and scrappy” he takes things even further. Pete’s extreme cleansing measures, as well as destroying many creatures habitat, result in him being unable to find his way home and after a hungry night spent in the bowl of a cement mixer, he finally sees his mistake. It really helps to pay close attention to the images in this story. The expression on the animals faces as Pete gives them a bath, the flower in the bin, the pile of bin bags, the hoover in the forest, the price tags on the trees…

Pete the badger is obsessively tidy. It’s bad enough that his obsession encroaches on his friends personal space but then he turns his attention to cleaning up the environment… and when scrubbing and polishing rocks and picking up every single fallen autumn leaf creates a mound of plastic bags and results in the trees looking “bare and scrappy” he takes things even further. Pete’s extreme cleansing measures, as well as destroying many creatures habitat, result in him being unable to find his way home and after a hungry night spent in the bowl of a cement mixer, he finally sees his mistake. It really helps to pay close attention to the images in this story. The expression on the animals faces as Pete gives them a bath, the flower in the bin, the pile of bin bags, the hoover in the forest, the price tags on the trees… A girl named Curly is in a bad mood and happens to come across a stick which has randomly fallen to the ground. The stick comes in handy for poking her little brother and happily also relieves her of her bad mood – which has been now passed to her mum. The bad mood is passed on further and so is the stick the stick finds an unlikely home in an ice cream parlour window whose owner keeps it there because it makes him happy.

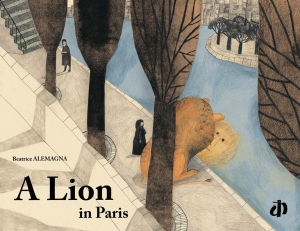

A girl named Curly is in a bad mood and happens to come across a stick which has randomly fallen to the ground. The stick comes in handy for poking her little brother and happily also relieves her of her bad mood – which has been now passed to her mum. The bad mood is passed on further and so is the stick the stick finds an unlikely home in an ice cream parlour window whose owner keeps it there because it makes him happy. A lion, big curious and bored decides to leave the grasslands in search of something more – a job, love and a future. Arriving in Paris by train he is a little daunted by the busy city. He thinks that he might surprise the Parisians but instead they surprise him – by taking no notice. As he takes in more and more of Paris he grows to love the city and decides finally to give up his freedom and his grassland home for a plinth in the middle of a busy roundabout.

A lion, big curious and bored decides to leave the grasslands in search of something more – a job, love and a future. Arriving in Paris by train he is a little daunted by the busy city. He thinks that he might surprise the Parisians but instead they surprise him – by taking no notice. As he takes in more and more of Paris he grows to love the city and decides finally to give up his freedom and his grassland home for a plinth in the middle of a busy roundabout. This small format picture book written in 1930’s poignantly tells the story of how the author’s writing desk puts on two pairs of shoes, (a pair belonging to him and a pair belonging to his wife) and takes off down the stairs out of a man-made urban environment and back to the woods where it takes root.

This small format picture book written in 1930’s poignantly tells the story of how the author’s writing desk puts on two pairs of shoes, (a pair belonging to him and a pair belonging to his wife) and takes off down the stairs out of a man-made urban environment and back to the woods where it takes root.